Doctors pioneer enhanced MRI scan for babies with brain injury

Currently, babies treated for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) receive a scan after five days which can show the severity of injury to the brain and is helpful in predicting severe neurological issues such as cerebral palsy.

However, more subtle problems that may affect children later in life, such as school performance, are difficult to identify.

HIE, which affects around one in 1,000 newborns in the UK, develops when a baby’s brain does not receive enough oxygen and blood around the time of delivery.

Initial treatment for moderate to severe HIE includes therapeutic hypothermia - cooling the baby from 37 to 33.5 degrees for 72 hours - which is delivered on specialist neonatal intensive care units such as the one in Southampton.

This improves survival rates and reduces the risk of severe neurological impairment, such as cerebral palsy and severe developmental delay, but affected babies remain at risk of more subtle problems which can affect school progress and emotional function.

This is currently monitored through follow-up appointments until the age of five where a range of tests and assessments are performed to determine the a child’s level of developmental progress.

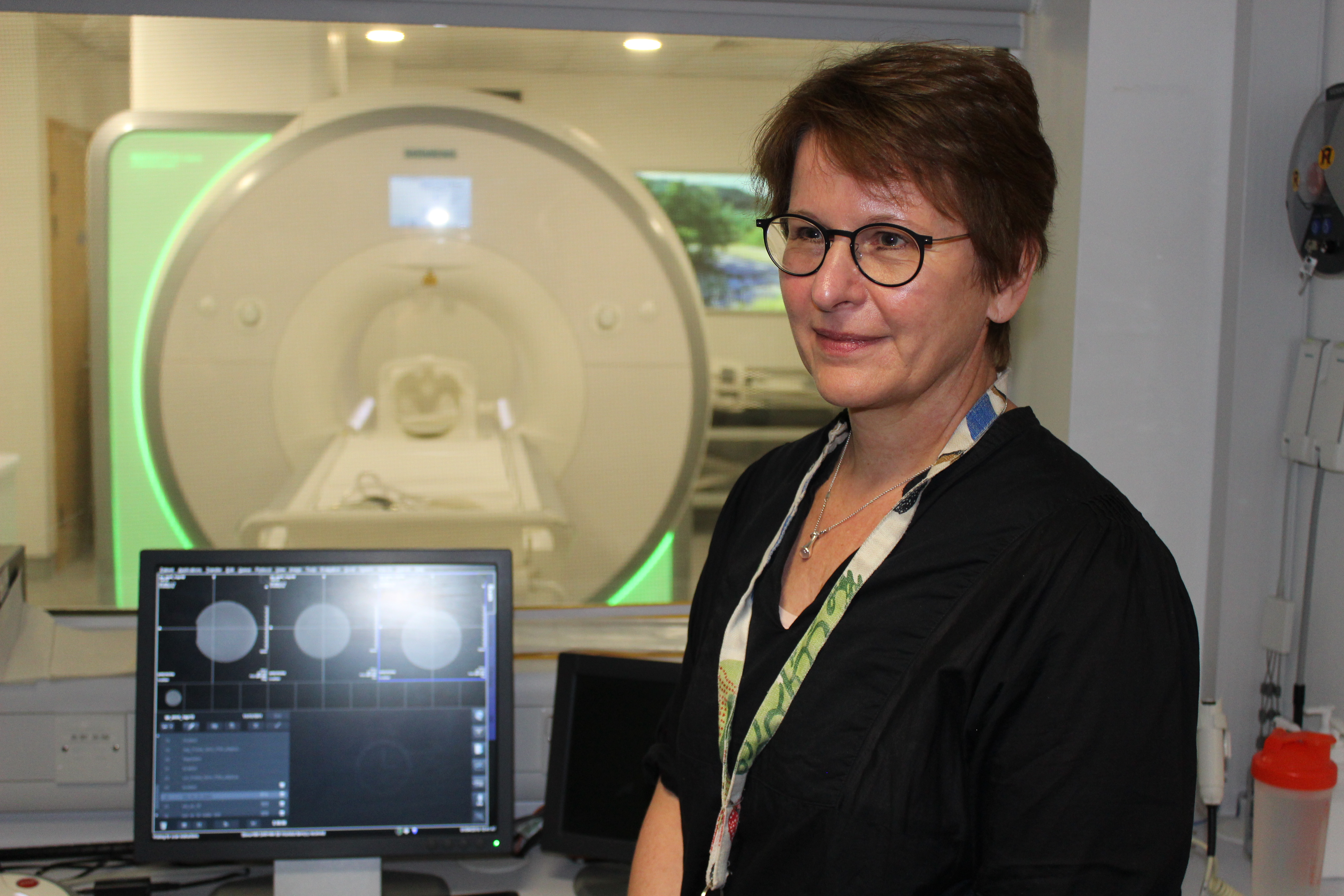

Now, clinicians and scientists, led by Dr Brigitte Vollmer, a consultant in neonatal neurology, at Southampton Children’s Hospital are extending and adapting the MRI to measure blood flow and neural connections, known as the wiring or mapping of the brain.

“Early evaluation of the severity of HIE is important to guide treatment, advise parents about the future of their newborn child and to facilitate testing of new treatments such as individually tailored early intervention, but current evaluation methods are imperfect,” explained Dr Vollmer.

“While the standard MRI scan provides some information on severity of brain injury and potential outcome of severe neuromotor impairment, it is not sufficiently sensitive with regards to accurate assessment of brain injury and outcome prediction of more subtle but nevertheless relevant problems later in life.

“We will investigate how non-invasive measurement of tissue perfusion, cellularity and neuronal connectivity using MRI can improve accuracy of the evaluation of the brain injury caused by HIE and how this relates to later neurodevelopmental outcomes.”

The new MRI techniques will be added to the end of the standard scan, with babies asleep and unaware of the additional tests.

Dr Vollmer added: “We will investigate whether or not there is a correlation between the results of measurements made in sensitive brain regions and how children progress with their development.

“If that proves to be the case, we will be able to accurately predict the longer-term prognosis for these babies and intervene sooner to address issues that are likely to develop later on.”

The £7,800 project is being funded by Southampton Hospital Charity. For more information or to donate visit www.justgiving.com/campaign/SouthamptonHIE